This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I have seen many studies recently that employ generative AI (such as ChatGPT), and I'm trying to tangle with the question of how this is going to change healthcare. How will we integrate these new tools into our practice? I'm going to talk about one of those studies, but I thought it would be a good opportunity to consider the bigger picture of how generative AI will change medicine.

Let's talk about what we mean when we say generative AI as opposed to whatever the alternative is. I'm calling it nongenerative AI or you might call it typical AI. The way we have used machine learning and AI in medicine is taking a lot of data and compressing it down into a single output. You take a bunch of data from the electronic health record or from genomic data or wherever your data sources are — a bunch of inputs — and you make a prediction at the end, a single number that tells you, for example, the chances that this patient is going to die in the next year or will develop diabetes in the next 6 months. It's fundamentally reductionist. That's where AI in medicine has been for a long time. You take an x-ray, which provides a ton of data, and compress it into whether the diagnosis is pneumonia — yes or no. It's a binary type of assessment.

Generative AI is different, although the architecture is somewhat the same. You're taking inputs, which can be multiple, although in general they are just text-based prompts. Instead of compressing those inputs down to a single output (eg, yes or no diabetes), you are creating multiple outputs. You're actually creating more in terms of output than you put in to begin with.

I put in a prompt to a generative AI that said "serious doctor discussing artificial intelligence." And I got this, which is not bad. He looks somewhat concerned.

So how do we use generative AI, something that expands on the data we have available as opposed to reducing the data we have available? Let's talk about ChatGPT, the most famous generative AI out there. It's fun to play with and it's a pretty decent test taker.

Studies have shown that if you just feed questions from, for example, a college-level microbiology exam and let ChatGPT pick the answers, you're going to score about 95%, which is obviously pretty good. Multiple studies have shown that ChatGPT can pass the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1. Highly impressive.

But ChatGPT didn't pass all exams. It failed the gastroenterology self-assessment test, for example, with 64% (passing requires 70%). The ophthalmology practice test — 50%.

This is transient. I have no doubt that as more data are fed in and as these devices are optimized to take tests (remember, they weren't built to take tests at all) we will see much higher scores. Saying "we're still better test takers" will only be true for a brief moment in time.

But the practice of medicine is not a multiple-choice test. When you have a patient in front of you, they don't give you five options of what the diagnosis might be or what the next appropriate test is. They may also present you with a lot of information that isn't relevant or may even be incorrect. A patient may tell you something that they are mistaken about but which might lead you down the wrong path. It's much more complicated than a standardized test.

So, my question is, how do we use this tool to make our lives easier? A paper came out this week in JAMA Internal Medicine that prompted me to put this talk together. This is one way that I think we can make friends with the robots. But to do that, we need to talk about medical notes.

So, documentation of what we do when we see patients is obviously very important. And there are many purposes to medical notes, right? They serve as a reminder to the providers themselves. What have we discussed with the patient? What do we think is going on? We're seeing hundreds of patients. It's nice to look back at your notes and see what the thought process was and to move the case forward. Obviously, notes are important for communication with other providers. What do I think is going on? What's our plan? What's moving forward?

Notes are incredibly important for medical billing. The level at which you can bill a visit depends critically on the elements in the notes. Unfortunately, that has corrupted our notes to some extent. They are chock-full nowadays of stuff that is really extraneous to direct care of the patient to show that we spent enough time with the patient to justify a certain billing classification. The meat of the note could be much shorter. That's a real problem.

In fact, we have good data to show that notes have a lot of problems. One of the most important is copying and pasting.

This study that came out in 2022 looked at thousands of medical record notes and determined how much of each note was copied and pasted from a prior note. As you can see here, in terms of progress notes, particularly in patient progress notes, two thirds of the content of the entire note was copied and pasted from the other notes. On the right hand side, you can see that the longer the medical record is, the more of any given note is copied and pasted.

I have seen this as an attending here at Yale-New Haven Hospital, where we have amazing medical students. Nevertheless, they're very busy. The temptation to copy and paste is there, and I see things in the medical record that are no longer true although they were once true. We were treating the patient for C diff, but we are no longer treating them for C diff. That is a direct result of copy and paste. Medical notes are a mess. In part it's because we're forced to put so much in there that doesn't actually communicate our plan to other providers or ourselves. It's there for medicolegal and billing reasons.

So can ChatGPT write your history of present illness (HPI) note? A study that came out in JAMA Internal Medicine compared HPI summaries generated by a chatbot and senior internal medicine residents. The question is whether the computer can do this for us, perhaps saving time and frustration at constantly being inside the medical record.

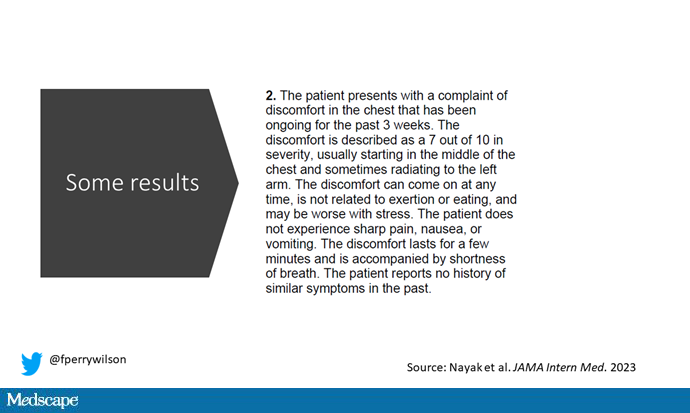

Here's how the study worked. The team wrote scripts of a discussion that a doctor might have with a patient — an in-person discussion — that thing that AI can't do because they aren't yet physically embodied. But we are, and you can see a sample script here.

This is when the doctor asks, "What brings you here?" The patient says, "I'm having some discomfort in my chest and I'm worried about it. I thought I better see a doctor. So here I am." They talk about how severe it is and whether it's a pressure or a tightness. Does it radiate? These are all of the classic chest pain questions you would ask if you saw a patient like this. These scripts were given to senior medical residents who had to write an HPI. You know — "the patient presents with a chief complaint of chest pain" and so on.

The script was also given to ChatGPT.

The researchers had to work to get good HPIs out of ChatGPT. Remember, ChatGPT is very general. It's not designed to write HPIs. You have to give it a prompt. The first prompt was pretty basic: "Read the following patient interview and write an HPI. Do not use abbreviations or acronyms."

They had ChatGPT generate multiple HPIs from this prompt. Remember, there's a randomness with these generative AI tools. With every prompt, you are going to get a slightly different output.

The number 2.03 was the mean number of errors per HPI. I'll show you an example of an error in a minute. They had to refine the prompt a little bit to remind ChatGPT to use standard medical terminology and language that is typically found in medical notes. There were still a fair number of errors until they said, "Include only information that is explicitly stated by the patient. Do not include information about age or gender unless explicitly stated."

Now we are getting to a very specific prompt to try to get ChatGPT to output something that we like. So, using that prompt, they generated 10 HPIs, and then they picked one that was particularly good. This is highly selected. This isn't "throw stuff into a chat bot and get an HPI."

They mixed ChatGPT's HPI with a bunch of HPIs by residents and asked the senior attendings if they could tell the difference.

Here's an example of an HPI written by ChatGPT about the chest pain patient.

Fine, right? If I saw this in a medical record, I probably wouldn't immediately think that an AI wrote it. It seems perfectly reasonable to me.

There were inaccuracies.

Remember, ChatGPT works by predicting the next word based on prior words it has seen. It's based on likelihood, on the tremendous amount of data it has seen in the past. It started the HPI by saying that the patient is a 59 year old male, but age and gender were not provided in the script. This is such a critical insight. Why did ChatGPT add age and gender? It's because it has read a lot of HPIs, and in most if not all of those HPIs, they open with "The patient is a 73-year-old female" or "The patient is a 22-year-old male." The patient's age and gender are almost always there, so ChatGPT knows it is supposed to include those facts.

ChatGPT isn't designed to ensure its own accuracy. It's designed to create something that seems human, like a human wrote it. It knows that HPIs are supposed to start with the patient's age and gender, so it throws in an age and gender, even though that information is incorrect. They had to update the prompt to say "Please don't write anything about age and gender unless it is specifically mentioned." That's called hallucination, and it is doing it to make its output seem more intelligible to a human, but essentially it's lying.

Another example: ChatGPT wrote that the patient's symptoms have not been relieved by antacids, but in the original patient script, the patient says that antacids hadn't been tried. Again, if you read the output, you would think it was reasonable. But if you know the input, you can see that ChatGPT made a mistake. If you think about having AI write your HPIs, remember that you won't have access to the medical interview used to generate the HPI. The concern about accuracy is obviously huge here.

But this is going to be overcome in the near future. I want to point out, first of all, that ChatGPT is not designed to write HPIs, but others designed to do so exist. Whole companies have been built to listen to medical interviews and generate HPIs that are much better tuned than just throwing stuff into ChatGPT and playing with your prompts until you get good output. This is not an existential problem for AI. This is actually quite a fixable problem and it will be fixed in the near future.

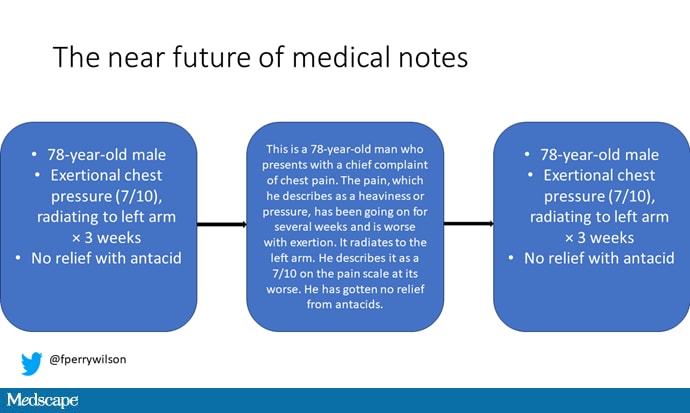

What do I think is going to happen? Imagine that our notes become highly information driven. That platonic, pure medical note, which doesn't have all the nonsense for billing and medicolegal reasons, will contain just the key important information that you want. You could write that note and then let the AI add all the other nonsense that the note needs. That could happen. You've got the bullet points here and then the AI goes here.

You might think, Oh, well, we could probably have AI write medical notes too, and summarize only the salient points for the doctor. In fact, those long medical notes are used by almost no one. The doctor writes the important stuff, and then AI adds stuff for billing and medicolegal reasons, and then it comes out on the other end.

That sounds a little tongue-in-cheek, but I think this is actually how AI changes how we write writ large. What these large language models show me is how much extraneous stuff is found in our writing, how many flourishes and unnecessary transitions and words that don't necessarily even convey emotion. Hemingway doesn't use these flourishes, and his writing is not boring. It is very human. These large language models actually force us to write better — more succinctly and more powerfully. Don't just stretch one paragraph of information into two pages, like you're writing a book report in the 7th grade, which is how a lot of these large language models feel.

Maybe the real far future of medical notes is that we make them useful again. Large language models translating to and from medical notes quickly become ridiculous. We start to realize that we should use these things for what they were originally intended to do, which is taking care of patients. There's a lot left. I don't think we're getting replaced by generative AI. In fact, I think it's going to make us better and will trim a lot of the fat from the system as we realize that if something can be done this easily by an AI, then it's probably not that valuable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 2: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 3: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 4: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 5: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 6: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 7: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 8: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Medscape © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: F. Perry Wilson. How AI Could Banish the Nonsense From Medicine - Medscape - Jul 17, 2023.

Comments